COMMENTS ON THE ART MARKET

November Hours

For the month of November, the gallery will be open Tuesday – Friday from 10 am – 5:30 pm, and all other times by appointment. Please note that the gallery will be closed on November 25th & 26th. And do not forget, we are always available by email and telephone ... so feel free to contact us if you have any questions.

Happy Halloween

Wishing everyone a Happy Halloween. It is time to put on your favorite costume (you cannot go wrong with a Superhero), get a few treats (Hershey's Kisses are yummy), and toast the Fall season with a nice tall glass of beer.

____________________

Gallery News

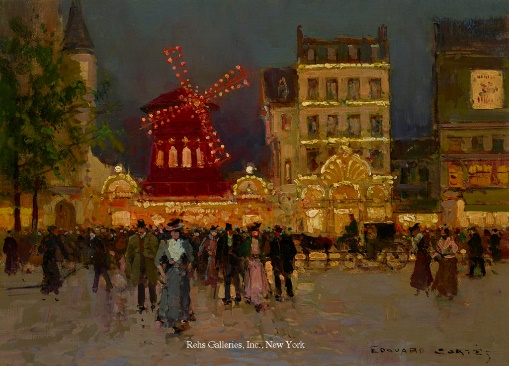

Another Rare Moulin Rouge By Edouard Cortès Surfaces

By: Howard

I am sure you can guess that as the foremost dealer in the work of Edouard Cortès, we are continually receiving emails from people offering paintings for sale. A majority of them are either very late examples or, sadly, not authentic. However, every so often, we get the real thing. Recently, an individual whose parents had purchased a painting by Edouard Cortès decades ago contacted us. When the photo arrived, we were shocked to see that it was one of his rarest and most sought-after subject matters — the Moulin Rouge! In addition, it was in original (untouched) condition. Yes, we bought it.

I am sure you can guess that as the foremost dealer in the work of Edouard Cortès, we are continually receiving emails from people offering paintings for sale. A majority of them are either very late examples or, sadly, not authentic. However, every so often, we get the real thing. Recently, an individual whose parents had purchased a painting by Edouard Cortès decades ago contacted us. When the photo arrived, we were shocked to see that it was one of his rarest and most sought-after subject matters — the Moulin Rouge! In addition, it was in original (untouched) condition. Yes, we bought it.

At this point, nobody knows how many Moulin Rouge scenes Cortès painted during his long career, but to date, we have only seen six … three of which the gallery bought and sold. You can read the Forbes article about another one we uncovered in 2019: Pair Of Edouard Cortès Paintings, Including Remarkably Rare ‘Moulin Rouge’, Quickly Acquired By Elite Collector From World Expert After Six Decades Unseen.

The Moulin Rouge, or the Red Windmill, was one of Paris’s most famous cabarets of the Belle Époque period. It opened on October 6, 1889, in the Montmartre district to provide an entertainment venue for people of all classes. The shows put on at the Moulin Rouge featured some of the most popular acts in France in the late nineteenth century, including Le Pétomane and Colette, as well as can-can dances and operettas. It became an entertainment destination for the European elite, including the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII. It also became a gathering place for artists, most famously Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who created posters on behalf of the venue. Sadly, the original house burned down in 1915 but was rebuilt and opened again in 1921. Today, it is considered the most famous cabaret in the world and one of the most popular tourist attractions in Paris.

The gallery created, for your enjoyment, three virtual exhibitions featuring the art of Edouard Cortès:

Paris: Part I

Paris: Part II

Country Life: Scenes in Normandy & Brittany

____________________

Stocks & Crypto

By: Lance

With last month’s losses and a rough first few days of the month, some may have been a bit concerned… and for good reason! I had no idea the extent, but there’s a lot of negative history between the stock market and October. For some reason, it’s the most volatile month on average, dating back to the start of the Dow Jones in 1896… even after you take out 1929 and 1987 – the years with the two worst crashes, both of which happened in October – the month still oddly ranks as the most volatile on the calendar. I can’t find any solid explanation as to why the trend persists – perhaps the market just likes to get festive for Halloween and scare everyone.

Fortunately, the immediate concerns were all for naught as the major indexes climbed steadily through the month and closed out at new record highs. But to be frank, I’m not sure it’s such a great thing… the market seems more and more detached from reality – I mean, I regularly read about supply chain issues the global economy is dealing with, an untamed pandemic, and a congress that struggles to pass a budget for more than a month at a time. I guess you just keep riding it til the wheels fall off kinda thing? Does anyone know how this actually works?

For October, the Dow Jones was up 5.6%, the S&P500 was up 6.7% and the NASDAQ was up 6.9%, - making up for September’s losses and then some! The Euro saw some light fluctuations relative to the dollar but ultimately ended the month back where it started, around $1.15; the Pound strengthened a bit, now sitting at $1.37 (up 1.6%). Gold remained fairly stable, up just 1.6% to $1,785; but crude continues to climb to heights we have not seen in years… futures are up 9.6% on the month, to $83.22/barrel. I’m glad I don’t drive – yikes!

On the other side of reality is the crypto world… I use the term reality loosely. I can’t believe we are talking about something called a Shiba token in any serious capacity, but here we are – “alternative” or “alt” coins that are earning insane returns based on nothing as far as I can tell – if you had scooped up $1,000 worth of Shiba back in April, it would be worth more than $65K today! That said, some of the mainstream tokens are all up at record highs after a choppy couple of months… Bitcoin topped out at $66.9K, and currently sits at $62K – up more than 50% from last month. Etherum too is up more than 50%, at an all-time high of $4,406. Litecoin is still well off the high it saw back in May but gained 40% in October as it is flirting with the $200 level.

As for my picks in the corporation casino, it was mixed… 8 up, 7 down. Airbnb (ABNB – month +2%); American Well Corporation (AMWL – month -1%); Aurora Cannabis Inc. (ACB – month -4%); Beyond Meat, Inc. (BYND – month -6%); Blink Charging Co. (BLNK – month +11%); Churchill Capital Corp IV (CCIV is now trading as Lucid Group LCID +46%); Canopy Growth Corp. (CGC – month -9%); Cronos Group Inc. (CRON – month -8%); FuelCell (FCEL – month +10%); Fisker Inc. (FSR – month +19%); Microvision (MVIS – month -31%); Nikola Corp (NKLA – month +11%); QuantumScape Corp (QS – month +18%); Under Armor, Inc. (UAA – month +9%); and Zomedica Corp. (ZOM –month -3%). Probably would have more fun taking your money to Vegas.

____________________

The Dark Side

By: Alyssa & Howard

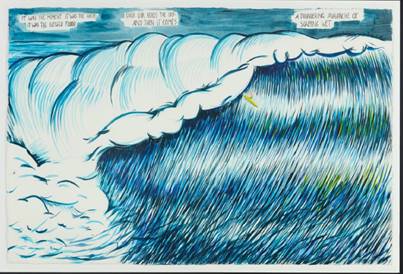

Dark Side Of The Art World - Forgeries

Federal charges have been brought against artist Christian Rosa Weinberger for selling forged Raymond Pettibon paintings. According to the law enforcement agencies involved, from 2017 through 2020, Weinberger and several co-conspirators sold several fake paintings from Pettibon’s Wave series to unsuspecting individuals whose names have not been released. Weinberger then used the proceeds from some of the sales to buy a home in California.

Federal charges have been brought against artist Christian Rosa Weinberger for selling forged Raymond Pettibon paintings. According to the law enforcement agencies involved, from 2017 through 2020, Weinberger and several co-conspirators sold several fake paintings from Pettibon’s Wave series to unsuspecting individuals whose names have not been released. Weinberger then used the proceeds from some of the sales to buy a home in California.

The whole scam began to unravel back in January when Nate Freeman published an article in Wet Paint discussing a supposed Pettibon work that was offered in 2020 for about $1 million. Dealers who saw the work were suspicious of its authenticity, and soon determined that it was most likely an unfinished work taken from Pettibon’s studio by his friend Christian Rosa Weinberger.

According to a press release from the U.S. Department of Justice, on the day after the Wet Paint article was published, Weinberger emailed one of his co-conspirators that the “secret is out.” Over the next few months, Weinberger had left the United States, then “sold the California residence and attempted to transfer the funds abroad.” He is still on the run.

You might be wondering why Weinberger would do this to an artist friend? Well, his career is a beautiful illustration of what goes on in the upper end of the contemporary market. More than a decade ago, he was basically unknown. With the rush of dealers and collectors looking to find the next hot artist, he soon became one of the art world’s darlings. His prices went from basically nothing to over $200,000. In 2014, Christie’s sold Untitled for $209,000. Just a year later, his works were selling for far less. In fact, Untitled was resold at Sotheby’s in 2017 for only $30,000. Those collectors and dealers who got in very early and sold quickly made a boatload of money. Everyone else was left holding the bag! While we could say that Weinberger and his art were victims, it still does not excuse his actions. This pump and dump scheme has been happening in the art world for far too long, and it is sad to keep watching it happen.

____________________

Artist’s In-Sights

Todd M. Casey & Yin Mn Blue

By: Todd

It’s not all that often that a new color is available in the art world. Blue pigments in art have always been precious, with Smalt, Egyptian blue, and Lapis lazuli being the three most commonly used in painting for centuries. Other blues have been introduced in the last 200 years, like Ultramarine, Cobalt, Prussian, Cerulean, and Phthalo blue. That all changed in 2009 when Mas Subramanian accidentally invented a new blue at Oregon State University. The new blue color is YIn Mn Blue and consists of the three metals; Yttrium, Indium, and Manganese.

Over the past 12 or so years, this color has grabbed headlines in the art world as — the new blue. So in 2020, Gamblin oil paints (also in Oregon) were able to get their hands on some of the pigment, mixed it with linseed oil, and offered a small run of about 160 tubes of Yin Mn Blue; thankfully, I was able to get my hands on one. Right out of the tube, it resembles Cobalt Blue, but when mixed with titanium white, the color pulls toward violet (similar to Ultramarine Blue when mixed). Overall, the color has weak tinting strength, meaning it is weak when mixed with a color.

After running these tests to see what predictions could be made from the new blue, I decided to take it for a test spin. The results were a gorgeous blue pigment that brightens up a painting and dries fast. I’ve painted two works with this new blue, the Dirty Martini (sold) and the Gimlet (illustrated here). These paintings will be featured in Cocktails, A Still Life: 60 Spirited Paintings and Recipes, a new book scheduled to be released next summer through Running Press.

You can also see Todd Casey’s YInMn Blue video HERE.

Beth Sistrunk’s Zero Calories Series – Caramel Popcorn

By: Beth

The Zero Calories series is all about nostalgia, happiness, and a celebration of the delicious, whether it’s pastry and other confections or favorite candies. For example, “Caramel Popcorn” is inspired by a memory of movie night from when I was six years old.

The Zero Calories series is all about nostalgia, happiness, and a celebration of the delicious, whether it’s pastry and other confections or favorite candies. For example, “Caramel Popcorn” is inspired by a memory of movie night from when I was six years old.

Bing!

I eagerly watch as my mother removes the bag of Orville Redenbacher popcorn from the brightly lit microwave.

Pings and pops make me jump as the popcorn continues to explode in the hot bag when she shakes it.

When the popcorn quiets, she tears open the paper, and steam erupts, coating her glasses in fog.

Somehow that always happens.

A giggle escapes my lips.

I want to dive right into the treat, but it’s not ready yet. This recipe calls for a special addition

.

I bounce up and down, holding the foil package containing the final garnish for the popcorn. The caramel inside is warm and deliciously squishy in my hands. I hold up the packet, and mom carefully slices the top with kitchen scissors.

“I want to do this part,” I say, and she holds the hot popcorn bag out for me, and I squeeze the toffee-colored caramel onto the popcorn and watch as it melts a little. The sweet-smelling caramel aroma blends with the savory popcorn, and my mouth waters so much I have to swallow.

Much to my disappointment, it doesn’t melt enough. I don’t want to miss my favorite part of the movie.

“We’re going to be late.”

“We have time.” Mom pops the whole thing back in the microwave for a bit before pouring our snack into a bowl.

We race to the couch just as Dorothy starts to sing about rainbows and birds on the TV. But, she was right, we’re not too late, and I tuck under her arm, and we both reach for the popcorn.

I close my eyes to savor the sweet and salty confection, the slightly crunchy popcorn, and the soft caramel melting in my mouth. I’ve got caramel stuck to my fingers, and at this point, my shirt, but I don’t care. It’s sooo good, and I can’t help but notice mom’s loving it too.

I tear myself away from the caramel popcorn, not wanting to miss a second of what comes next.

|With a thump and an “oh,” the house on the TV falls down. Everything goes from a dismal black and white to full color, and it gives me goosebumps again, just like last time.

The scent of caramel and popcorn always reminds me, “there’s no place like home.”

____________________

Really?

By: Amy

The Bridge At Pooh Corner

Alan Alexander Milne (1882 – 1956), often referred to as A.A. Milne, was an English author best known for his books about the adventures of his son Christopher Robin and his stuffed animals, most notably, the lovable teddy bear, Winnie the Pooh. The stories and poems in Milne’s books take place in the fictional Hundred Acre Wood, inspired by the Five Hundred Acre Wood in Ashdown Forest in East Sussex, England, where the Milne family lived. I have always had a warm spot in my heart for Winnie the Pooh. I don’t remember when I first fell in love with Pooh, probably when I was six… and my all-time favorite poem was on the last page of Milne’s book Now We Are Six, (the poem has the same title) a collection of thirty-five poems published in 1927. I only have a few items in my Pooh collection, but I am always looking for that exceptional item to add to it. So, when Howard told me that the infamous Poohsticks Bridge was just sold, I was more than a little disappointed that it would not end up in our backyard; after all, if London Bridge can be moved to Arizona, why couldn’t Poohsticks Bridge be in New York? However, I seriously doubt our backyard would be large enough for a bridge, even if it’s only 30 feet long and 15 feet wide.

Poohsticks, a game created and played by A.A. Milne with his son, Christopher Robin, was first mentioned in the 1928 book, The House at Pooh Corner. Milne and Christopher Robin began playing Poohsticks in Ashdown Forest (The Hundred Acre Wood) on a bridge built in 1907 called the Posingford Bridge. The game was simple; drop a stick or acorn on the upstream side of the bridge, and the person (or character) whose stick appears first on the downstream side wins. The bridge became such a popular destination in the Hundred Acre Wood that a campaign started in the late 1970s to rebuild it; it was so worn down from the overwhelming number of visitors. They were able to do a partial rebuild in 1979, and Christopher Robin Milne officiated the bridge’s reopening and renamed it Poohsticks Bridge.

In 1999, the East Sussex city council appealed to local businesses and the Disney Corporation, who agreed to make a substantial donation to assist in the complete recreation of the bridge. The original bridge was put into storage and a short time ago was reconstructed with any original parts that could be used and some similar-aged timber; the council then decided to auction it. It was estimated to make £40-60K ($55-80K), and in the beginning of October, potential buyers submitted sealed bids. The bridge undoubtedly surprised everyone when it sold for £101K (£131K/$179K w/p).

The wonderful thing about the sale is that the buyer was William Sackville, Lord De La Warr. His family has owned two thousand acres of land known as Buckhurst Estate for about 900 years; a portion of his land is the famous Hundred Acre Wood. Lord De La Warr recalls his father’s stories about playing Poohsticks with Christopher Robin and his renowned bear, so the bridge is very dear to him. He has promised that he will take great care of the bridge and hopes that adults and children will continue to admire and visit it.

You can still play Poohsticks on the newly built bridge in Ashdown Forest, although you must bring your own sticks, so you don’t damage the trees in the forest. The game became so popular that there has been a World Poohsticks Championship held at Day’s Lock on the River Thames in Oxfordshire, England, since 1984.

Sphinxes Surprise Saleroom

Wouldn’t it be nice to find out that something you have had in your possession for years, that you assumed was worthless, turned out to be the real deal? That is what happened to one lucky family in the United Kingdom. The family was moving to a new home and decided to sell some of their belongings including a pair of carved stone statues of sphinxes – mythical creatures with a lion’s body and a human head, that had been in their garden for years.

Wouldn’t it be nice to find out that something you have had in your possession for years, that you assumed was worthless, turned out to be the real deal? That is what happened to one lucky family in the United Kingdom. The family was moving to a new home and decided to sell some of their belongings including a pair of carved stone statues of sphinxes – mythical creatures with a lion’s body and a human head, that had been in their garden for years.

The family bought the sphinxes at an auction about 15 years ago for just a few hundred pounds. When they purchased them, they assumed they were 18th or 19th-century replicas of ancient Egyptian relics. Well, it turns out the heavily weathered garden decorations were, in fact, genuine ancient Egyptian artifacts. The auctioneer was unaware of the authenticity of the statues and gave them a pre-sale estimate of £300-500 ($407-680); after all, they were in rough condition sitting outside for years. One of the statues had been repaired using cement to re-attach its head.

The auction house stated there was modest interest in the items before the sale, but nothing would indicate how high the bidding might go. The lot opened at £200 ($272), but the price quickly escalated with interest from four telephone bidders and numerous online bidders. After the bidding frenzy finished, the buyer paid £195K/$266K (£242K/$330K w/p), setting a record for the auction house. The auction room later reported that the winning bidder was an international auction gallery; I am sure we will see these fine specimens surface again, and who knows what they will sell for the next time around!

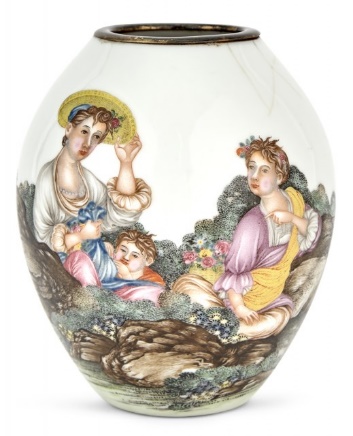

Damaged Vase Still Makes A Mark

One of the highlights of Asia Week in New York was a vase owned by Sarah Belk Gambrell, the heiress to the Belk department stores; she was 102 years old when she passed away in July of 2020. Gambrell created an extensive collection of porcelain; the sale of her collection far exceeded the auction room’s expectations.

One of the highlights of Asia Week in New York was a vase owned by Sarah Belk Gambrell, the heiress to the Belk department stores; she was 102 years old when she passed away in July of 2020. Gambrell created an extensive collection of porcelain; the sale of her collection far exceeded the auction room’s expectations.

The vase, known as a Falangcai vase, has a four-character mark in blue indicating that the Qianlong Emperor’s imperial workshop produced it. Falangcai, which translates to foreign colors, refers to porcelains painted in the imperial workshops, using enamels introduced from the West. Production of Falangcai ceramics began around 1696 and was made exclusively for the royal family; due to the high cost of production, the number of porcelain pieces produced was minimal. Among the small number of pieces still existing, most are now in the collections of museums worldwide; they are among the most highly sought-after works of the Qing dynasty.

The vase was just 4 7/8 inches in height and decorated with a scene of two European women with a child in a garden, which is highly unusual for Chinese porcelain but does illustrate the Emperor’s family’s infatuation with the West. Although the piece was damaged, the vase’s neck was completely missing, it still had a strong estimate of $100-300K. Bidding opened at just $50K and quickly shot way past the estimate; when bidding reached $90K, it made a giant leap to $1M and the hammer finally came down at $2M! ($2.45 M w/p). The vase alone exceeded the pre-sale estimate of $1M for the entire sale!!

____________________

The Art Market

By: Howard & Lance

The auction action ramped up this month, and we covered several of them (these are just a fraction of the sales that took place). Have no fear, there will be many more to cover in November, so stay tuned.

Christie’s European Art Part II

By: Howard

On the 15th of October, Christie’s online sale of mid to lower-level European art closed, and while some lots generated action, many others had a tough go.

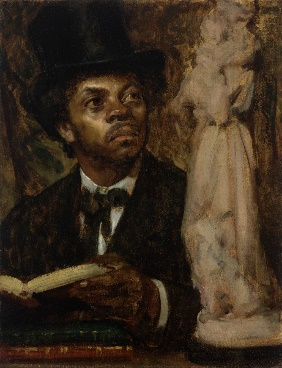

The most expensive work in the sale was a bit of a surprise. Léon Herbo’s small (14.75 x 11.5 inches) Portrait of an Art Connoisseur, possibly Ira Aldridge was expected to bring $20-30K and eventually hammered down at $110K ($137.5K w/p). I guess the figure could be Aldridge, but Herbo was born in 1850, and Ira Aldridge (an actor) died in 1867. That would mean that if Herbo painted it from life, he was just a teenager. It is also interesting to note that this painting came up in a European sale back in 2019. Then it was cataloged as Ecole du XIXe siècle L’amateur en haut-de-forme au vernissage d’un salon (19th-century school The amateur in a top hat at the opening of a salon), carried a €600-800 estimate and sold for €5,000 ($5,700); so that seller was very happy!

A collaborative work between Jean B.C. Corot and Jules Antoine Demeur took second place. Arleux-du-Nord—le bord des clairs was painted in 1871, had an estimate of $40-60K, and hammered at $75K ($94K w/p). This one surprised me a bit since it had some condition issues, was not a strong work, and had sold in October 2020 for $60K ($75K w/p). However, the painting that took the third spot was even more of a surprise (I would have bet that this one would not sell). Louis M de Schryver’s Paris – The Flower Market on the Île de la Cité was not one of the artist’s more impressive works. The painting was offered in 2019 with a $200-300K estimate, and in 2020 with a $120-180K estimate; both times it went unsold. Even though the painting has some serious condition issues, which included a good deal of inpainting on the central figure and the face of the woman on the far right, someone did not care and bought it for $70K ($87.5K w/p – est. $70-100K). Why?

In fourth place was Charles Daubigny’s Les Laveuses au bord de la Seine à Bonnière; a beautiful, tranquil landscape that generated a bit of interest and sold for $65K ($81K w/p – est. $30-50K). In fifth, there was a tie. Louis-Ernest Barrias’ bronze and marble sculpture Nature Revealing Herself Before Science (est. $30-50K), and Firmin-Girard’s Le quai aux fleurs et la tour de l’horlage (a small/weak work with a fair bit of inpainting in the sky – est. $20-30K) both sold for $55K ($69K w/p).

The only other work that generated strong interest was Alphonse Mucha’s Portrait of the Artist’s Daughter in Slavic Dress; a small chalk on paper estimated at $8-$12K that sold for $38K ($47.5K w/p). There were, however, many works that did not sell… these included paintings by Rochegrosse ($200-300K), Breton ($60-80K), Reekers ($60-80K), von Blaas ($60-80K), Sorolla ($60-80K), and Diaz de la Pena ($30-50K).

Of the 62 lots offered, 36 sold (58%), and the total achieved was $1.09M ($1.37M w/p). The presale estimate range was $1.68-$2.5M, so they fell short even with the buyer’s premium. Of the 36 sold lots, 14 were below, 10 within, and 12 above their estimate range, leaving an accuracy rate of just 16%.

When you are looking to purchase a work of art, you need to be smart. Buying something just because it looks good to the naked eye may not be a wise decision. As a buyer, you need to dig a little deeper. Find out about the work’s condition (not every painting is perfect, but you do not want those that have serious issues), and try to determine how the work fits into the artist’s oeuvre – when was it painted, is it a subject that people expect to see, etc. Some of us in the art world do not want to see people throw away their money.

Christie’s 19th C. European Art Auction – A Tough Go.

By: Howard

On October 13, Christie’s presented their European Art Part I auction, which included just 37 lots. We did go to view the sale; in fact, I went twice, and while there were some nice paintings, I was a little skeptical that overall, the sale would be a real success. (w/p = with the buyer’s premium)

The top lot was an awe-inspiring work by the British Victorian artist Herbert James Draper titled The Mountain Mists. The painting, which measured 85 x 46 inches, was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1912… it carried a $1.2-1.8M estimate and hammered for $1.65M ($2.01M w/p). The seller purchased the piece back in 2000 for $1.25M, so they made a little profit! Peder S. Krøyer’s Summer Evening on Skagen Beach, Portrait of the Artist’s Wife generated a bit of interest and hammered for $750K ($930K w/p), beating its $500-700K estimate; this landed the work in second place. The seller purchased the painting back in 1989 for $120K… they did well! Galloping into the third spot was Alfred Munnings’ After the Race, Cheltenham. This large and attractive looking painting came from the estate collection of Mrs. Elizabeth Moran (a thoroughbred owner and breeder); it was expected to bring $700-1M and hammered at $680K ($846K w/p). Mrs. Moran purchased the painting back in 1981 for $200K, so even though it did not reach the estimate, it appreciated nicely.

Rounding out the top five were William Bouguereau’s Retour des Champs at $610K ($762K w/p – est. $700-1M). This large, single-figure painting was last on the public market in 1992 and sold for $198K. It was purchased by a London dealer and sold to a collector in the US; the current seller was a relative. In the fifth slot was Sir Francis B. Dicksee’s 1901 Royal Academy painting Yseult. I remember when it was offered at a Sotheby’s sale in 2019 and found it a little sad looking – I still feel that way. In that sale, it was estimated at $1-2M and sold for $900K ($1.15M w/p). This time it was expected to sell between $800-$1.2M and hammered at $600K ($750K w/p)… I am sure the seller was not very happy.

There were only two works that sparked competitive bidding. The first was Adolph von Menzel’s Mondschein über den Dächern von Berlin. A small (12.5 x 7.5 inch) gouache on paper that was a restituted work and was being sold on behalf of the current owner and the heirs of Alfred and Gertrude Sommerguth. I must say that when viewing the sale, I paid very little attention to it, but at least two people really wanted it. Not sure why, but then again, what do I know? The work carried a $200-300K estimate and sold for $550K ($687.5K w/p)… so I am sure both parties were happy. The other was a small (12 x 9 inch) study of a jockey by Munnings. The painting was from the Moran collection, had a $15-20K estimate, and sold for $40K ($50K w/p).

There were only two works that sparked competitive bidding. The first was Adolph von Menzel’s Mondschein über den Dächern von Berlin. A small (12.5 x 7.5 inch) gouache on paper that was a restituted work and was being sold on behalf of the current owner and the heirs of Alfred and Gertrude Sommerguth. I must say that when viewing the sale, I paid very little attention to it, but at least two people really wanted it. Not sure why, but then again, what do I know? The work carried a $200-300K estimate and sold for $550K ($687.5K w/p)… so I am sure both parties were happy. The other was a small (12 x 9 inch) study of a jockey by Munnings. The painting was from the Moran collection, had a $15-20K estimate, and sold for $40K ($50K w/p).

Sadly, some pricey works went unsold. Among the more expensive were Julius Stewart’s The Hunt Supper (est. $2-3M), Bouguereau’s Tricoteuse (est. $1.2-1.8M), Munning’s Who’s the Lady? And Two Studies ($800-$1.2M), Segantini’s Ritratto dells signora Torelli (est. $600-800K), and Edward Hughes’ Wings of the Morning ($400-600K). Also, Gustav Bauernfeind’s Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives at Sunset (est. $2-3M), was withdrawn just before the sale. The funny thing is that the same painting was offered in a 2020 Sotheby’s London sale with an estimate of £3-4M and was also withdrawn.

When the short session finished, of the 36 works offered, 22 sold (a sell-through rate of 61%), and the total take was $8.09M ($10.05M w/p). The presale estimate was $12.9-$19.8M, so they were way short even with the buyer’s premium. Digging a bit deeper, we find that of the sold lots 9 were below, 6 within, and 7 above their expected range. When we added the unsold lots, this left them with an accuracy rate of just 16.6%.

We all want to see these sales succeed, so the main auction rooms must be very choosy with the works they offer. The estimates need to reflect the quality and salability of each piece, and those works with serious condition issues should be pushed to the side.

Contemporary Art Evening Sale – Sotheby’s Hong Kong

By: Lance

This past Saturday, Sotheby’s hosted a Contemporary Art Evening Sale in Hong Kong… the auction featured “a refined selection of exceptional masterpieces,” though you could probably debate the “masterpiece” status of a few of the lots.

This past Saturday, Sotheby’s hosted a Contemporary Art Evening Sale in Hong Kong… the auction featured “a refined selection of exceptional masterpieces,” though you could probably debate the “masterpiece” status of a few of the lots.

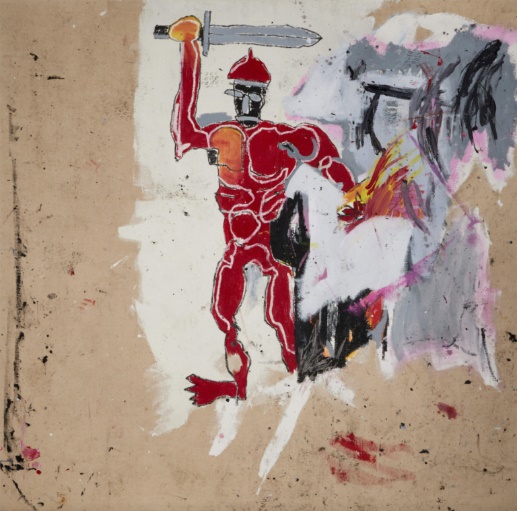

As expected, the top lot was Basquiat’s Untitled (Red Warrior)… it was a guaranteed lot with an irrevocable bid, so we knew it would sell. That said, it didn’t attract much additional interest and hammered at HK$ 143M ($18.4M), which was below the HK$ 150-200M estimate; the premium bumps that price up to HK$ 162M ($20.9M), so they needed it on that one.

Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara took second with his work Under the Hazy Sky… a 2012 canvas which was sold through Pace Gallery. This one was also guaranteed with an irrevocable bid and ultimately hammered at HK$ 61.5M ($7.9M); within the HK$ 55-75M estimate. While the premium wasn’t necessary to hit the estimate on this one, it would be needed for the sale overall – the premium pushed this lot up to HK$ 68.7M ($8.8M).

Close behind was Joan Mitchell’s Untitled – another guaranteed lot… this one hammered at HK$ 58.8M ($7.5M), on a HK$ 50-60M estimate; HK$ 65.2M ($8.3M) with premiums. This one last sold at Christie’s Evening Sale in New York back in 2004… at that time, it sold for just $477K!

There were a number of other lots that saw nice prices and impressive results… a work by Adrian Ghenie found a buyer at HK$ 54M ($7M), though that was guaranteed; and a Lichtenstein went for HK$ 48M ($6.1M). There were also lots like Rafa Macarrón’s Rutina Flour, which sold for HK$ 3.4M ($550K) – more than six times the estimate!

Once the premiums were added in, there were no lots sold below estimate – that was certainly a plus. That said, there were a few failures… four to be exact – works by Liu Wei (HK$ 10-20M), Jennifer Guidi (HK$ 1.6-2.8M), Zeng Fanzhi (HK$ 8-10M), and Banksy (HK$ 12-18M).

At the end of the session, 31 works were sold (88%) for a total of HK$ 586.8M ($75.4M) with premium… the sale’s estimate was HK$ 508.4-705.8M, so they were comfortably in their range. As I alluded to earlier, without the premiums they fall just short at HK$ 507.8. Don’t get me wrong, it was a solid result… it just didn’t have the fireworks you’d expect for an evening sale.

The London Impressionist and Modern Sale – Sotheby’s

By: Howard

Sotheby’s had another tough go on October 7th with their lower to mid-level Impressionist and Modern works of art. While there were a few nice paintings in the mix, there was nothing that made me say – “I gotta have that!” (w/p = with the buyer’s premium)

The top performer was a small (9.625 x 13.375 inch) sketch by German artist Max Liebermann, titled Spielende Kinder am Strand (Children playing on the beach). The work, which appears to have been fresh to the market, was expected to sell in the £50-70K range and hammered at £130K/$177K (£164K/$223K w/p). From the quick bit of research I did, it seems this is the highest price achieved for a small study; the previous high of $170K was set back in 2015. Next came Marc Chagall’s Nature morte devant la fenêtre (a 1953 brush and ink and wash on paper). The work was expected to bring £100-150K and hammered at £110K/$150K (£138.6K/$186K w/p). And in the third slot was Bernard Buffet’s 1956 Nature morte au réveil. I do like Buffet’s work, but sometimes they are a little too creepy for me. Expected to sell in the £45-65K range, this one eclipsed the upper end when it sold for £85K/$116K (£107k/$146K w/p). Filling in the top five were Lynn Chadwick’s sculpture Third girl sitting on bench at £70K/$95K (£88.2K/$120K w/p – est. £70-100K), and František Kupka’s Composition – Lueurs, a small pastel on paper, that brought £65K/$88.5K (£81.9K/$111.6K w/p).

Other good performers were Gustav Klimt’s Auf dem Bauch liegender Halbakt nach rechts (Semi-Nude Lying on her Stomach turned to the Right) at £32K/$43.5 (£40.3K/$55K w/p – est. £10-15K), Henri Hayden’s Paysage which brought £14K/$19K (£17.6K/$24K w/p – est. £3-5K), and Armand Guillaumin’s Le Ravin de la folie, vue de Chateau Crozant which hammered at £50K/$68K (£63K/$85.7K w/p – est. £15-20K). Some of the works that could not find buyers included Utrillo’s Eglise de Beaulieu (est. £60-80K), Boudin’s Deauville, le basin (est. £50-70K), Degas’ Jockey’s (£50-70K), Kisling’s Le parc (est. £50-70K), and Marquet’s Le Paquebot (£40-60K).

By the end of the sale, 97 lots were offered and 66 sold (a sell-through rate of 68%). The sale totaled £1.34M/$1.83M hammer (£1.69M/$2.3M w/p), while the presale estimate range was £1.65-2.5M, so they needed the buyer’s premium to make just squeak by the low end. Of the 97 lots, 17 were below, 32 within, and 18 above their estimate range. This gave them an accuracy rate of 33% … much better than the American sale.

The American Art Sale – Sotheby’s

By: Howard

On October 6th, Sotheby’s offered up a wide range of American paintings, spanning the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. I will say that there wasn’t anything for us, but then again, we only deal in a handful of American artists’ work. (w/p = with the buyer’s premium)

Taking the top spot was Indian Girl (Portrait of Lolita) by Nicolai Fechin (a Russian born artist who emigrated to the US in 1923, settled in New Mexico, and specialized in works featuring Native Americans). The Palm Springs Art Museum was selling the painting; it carried a $250-350K estimate and hammered at $240K ($302.4K w/p). Coming in second was Albert Bierstadt’s Park at Vancouver. The small, fresh-to-the-market oil was expected to bring between $25-35K, and when the bidding was over, it hammered for $85K ($107.1K w/p); I am sure the seller was thrilled. Taking third was a work by one of our favorite American artists, Guy Wiggins. Winter in New York carried a $30-50K estimate and hammered at $75K ($94.5K w/p)! Rounding out the top five were two paintings that did little for me. The first was Julian Onderdonk’s Untitled (Texas Hill Country Landscape) that carried a $50-70K estimate and sold for $70K (88.2K w/p), and a dark painting by William Merritt Chase titled Still Life – Fruit at $65K (81.9K w/p – est. $20-30K).

Taking the top spot was Indian Girl (Portrait of Lolita) by Nicolai Fechin (a Russian born artist who emigrated to the US in 1923, settled in New Mexico, and specialized in works featuring Native Americans). The Palm Springs Art Museum was selling the painting; it carried a $250-350K estimate and hammered at $240K ($302.4K w/p). Coming in second was Albert Bierstadt’s Park at Vancouver. The small, fresh-to-the-market oil was expected to bring between $25-35K, and when the bidding was over, it hammered for $85K ($107.1K w/p); I am sure the seller was thrilled. Taking third was a work by one of our favorite American artists, Guy Wiggins. Winter in New York carried a $30-50K estimate and hammered at $75K ($94.5K w/p)! Rounding out the top five were two paintings that did little for me. The first was Julian Onderdonk’s Untitled (Texas Hill Country Landscape) that carried a $50-70K estimate and sold for $70K (88.2K w/p), and a dark painting by William Merritt Chase titled Still Life – Fruit at $65K (81.9K w/p – est. $20-30K).

There were a handful of lots that performed well; these included Louis Stone’s 1938 Untitled (Abstract Composition) at $45K (56.7K w/p – est. $10-15K), Dwight William Tryon’s A Glimpse of the Sea (sold by the Brooklyn Museum) at $24K ($30.2K w/p – est. $5-7K), and Bouquet with Poppy, a small still life by William Glackens, that brought $32K (40.3K w/p – est. $12-18K). On the other side, too many of the higher-priced lots did not find buyers. In fact, of the ten highest estimated works in the sale, only three sold. Among the unsold works were Robert Henri’s Portrait of Mrs. Arthur Bond Cecil ($150-250K), Edward Redfield’s Frosty Morning (est. $120-180K), Milton Avery’s Dunes and Red Sea (eat. $100-150K), and Sanford R. Gifford’s The Arch of Nero at Tivoli (eat. $100-150K).

When the sale concluded, of the 109 works offered, 74 sold (67.9% sell-through rate), and the total hammer price was $1.93M ($2.44M w/p). The presale estimate range was $2.76-$4.08M, so they fell well short… even with the buyer’s premium added in, they did not make it. Of the sold works, 32 fell below, 16 within, and 26 above their presale estimate range, giving them an accuracy rate of just 14.7%. Next time you receive an auction estimate, realize that it is nothing more than a guesstimate.

____________________

Deeper Thoughts

By: Nathan

French Exit: A Rare Prayerbook And The Fate Of Jewish Cultural Heritage

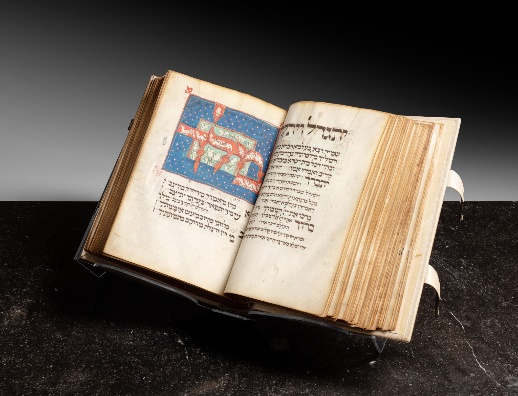

The auction room is where one can witness some once-in-a-lifetime moments. Having briefly worked at an auction house myself, there’s always a small thrill in seeing a rare item being fought over, ending with the sharp rap of the hammer. One of those moments recently took place at Sotheby’s when, on October 19th, a rare Jewish illuminated manuscript went for $8.3 million.

The auction room is where one can witness some once-in-a-lifetime moments. Having briefly worked at an auction house myself, there’s always a small thrill in seeing a rare item being fought over, ending with the sharp rap of the hammer. One of those moments recently took place at Sotheby’s when, on October 19th, a rare Jewish illuminated manuscript went for $8.3 million.

The Luzzatto High Holiday Mahzor is named after one of the book’s former owners, Samuel David Luzzatto, a nineteenth-century Italian rabbi, poet, and book-collector. It is an example of an extremely rare form of manuscript, as there are only about twenty medieval Jewish illuminated books known to currently exist. It is also now the second most valuable piece of Judaica to sell at auction, only behind the Bomberg Talmud, which was sold at Sotheby’s for $9.3 million in 20l5. Though the Mahzor’s buyer is anonymous, some experts have guessed that it is a prominent private collector based in the United States.

The book was created in Bavaria in the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century, but later found its way to Switzerland, France, and Northern Italy throughout its lifetime. It was a rare luxury item even when it was first produced, since movable type was not introduced to Europe until the Mahzor was nearly two-hundred years old. This means that every page of the book was written and decorated by hand by an extremely skilled artisan. To that artisan’s credit, the Luzzatto Mahzor is known to contain some of the greatest known examples of Hebrew calligraphy and medieval Jewish illustration. Furthermore, the annotations and edits allow us to gain further knowledge on the theological and cultural differences between different European Jewish communities.

Soon after Luzzatto’s death in 1865, the Mahzor found itself in the hands of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, a French Jewish education organization based in Paris. The AIU has expressed its intent to use the proceeds to fund educational programs and scholarships. Sotheby’s experts estimated the book to fetch anywhere between $4 million and $6 million. So, it was a great surprise when it was bought for over double the low estimate by an unknown collector.

However, the sale has a slightly darker side that few are mentioning. The sale of the Luzzatto Mahzor is indicative of Jewish treasures moving from public museums and libraries to private collections. The Sotheby’s sale was made, more or less, out of desperation. According to the AIU’s leading figures, like Marc Eisenberg and Roger Cukierman, the organization would not have had funds to operate past 2030 without the proceeds from the sale. Other Jewish organizations on both sides of the Atlantic are having to face similar situations, with New York’s Jewish Theological Seminary selling many of its resources over the past several years. There were even some who called for the French government to declare the Luzzatto Mahzor a national treasure to prevent the sale. Some have compared the book to the Mona Lisa regarding its cultural and artistic importance to Jewish people in Europe.

Some experts like Sharon Mintz, Sotheby’s senior Judaica consultant, believe that despite the Mahzor’s transference from a public European institution to a private American collection, the book will enjoy even greater recognition and visibility. She told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency that the speculated buyer “is known to be very generous in sharing his manuscripts with the public – they have been in many public exhibitions and the buyer also provides access to scholars.” Furthermore, the fact that the book reached such a high price at auction will add not only to its future value but has already added to public awareness of the Mahzor’s existence and importance. But even if the new owner is more restrictive regarding access to the Mahzor, there may be nothing to worry about. It’s possible that the piece won’t stay in private hands for long; that for tax purposes, the private collector will likely donate the Mahzor to a library or other public exhibit. So perhaps the fears of some may be unfounded; that the book “would disappear in a safe” for the foreseeable future.

Decisions In Revisions: Reimagining A Christopher Columbus Monument

One of the ways society expresses admiration is public memorialization. Busts, plaques, obelisks, and statues all have a prominent place in our culture. They can be something you pass every day, or an iconic piece of a city skyline. It can be something you pay no mind to, or something to which you attach deep personal meaning. But those revered by generations past might not have the same reputation today. Nowadays, many don’t feel entirely comfortable with the existence of certain glorious public monuments, some built decades or centuries ago, that represent the values of that era. Perceptions change over time, with yesterday’s heroes becoming today’s villains. While determining who remains memorialized is important, a trickier question remains: what do we do with those public artworks that we have decided cannot remain in public anymore?

One of the ways society expresses admiration is public memorialization. Busts, plaques, obelisks, and statues all have a prominent place in our culture. They can be something you pass every day, or an iconic piece of a city skyline. It can be something you pay no mind to, or something to which you attach deep personal meaning. But those revered by generations past might not have the same reputation today. Nowadays, many don’t feel entirely comfortable with the existence of certain glorious public monuments, some built decades or centuries ago, that represent the values of that era. Perceptions change over time, with yesterday’s heroes becoming today’s villains. While determining who remains memorialized is important, a trickier question remains: what do we do with those public artworks that we have decided cannot remain in public anymore?

While many agree that figures such as Confederate generals and prominent imperialists should not be publicly valorized, the question of what happens to their monuments remains a precarious subject. Some call for complete removal or even destruction, while others reject these proposals at face value. Some see that a compromise might be better. Just last weekend, Oxford’s Oriel College made just such a compromise, choosing not to take down a statue of the British imperialist and De Beers founder Cecil Rhodes. Instead, they installed a plaque nearby providing historical context. The plaque describes Rhodes not as a paragon of British virtue and industry, but as a “committed British colonialist” who frequently exploited indigenous Africans. While several solutions have been put forth, one compelling path was forged at a recent exhibition in Argentina.

The Biennial of Contemporary Art of the South, or Bienalsur, is an international art show based in Buenos Aires but held at multiple venues simultaneously across the globe. Its third edition this year is being held at 120 different venues in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Morocco, Spain, France, Saudi Arabia, and Japan, while the Brazilian, Italian, and German embassies in Buenos Aires are also offering spaces for exhibition. As part of Bienalsur, the Argentine sculptor Alexis Minkiewicz is currently showing his most recent work at the Manzana de las Luces, a historic cultural center in Buenos Aires. It is his own take on how to approach problematic memorials: a reimagining of the city’s controversial Christopher Columbus monument.

In 1921, a monument commemorating Christopher Columbus was unveiled in Buenos Aires. Antonio Devoto, representing the city’s Italian community, commissioned the work in 1910 for Argentina’s centenary celebrations. Over the course of those eleven years, the Italian sculptor Arnoldo Zocchi completed the Carrara marble pieces, which were then transported across the Atlantic and assembled in Argentina’s capital. The monument stands 85-feet-high, with Columbus atop a plinth looking out across the Río de la Plata. Reminiscent of the Roman public monuments designed by Bernini, the base of the plinth is surrounded by a whirlwind of figures fitting together like a Baroque pile-on. At the front, facing the river, a helmed female figure holding a torch is meant to represent civilization. To her left, a boyish angel points out across the water, like a lookout on the prow of a stone ship.

While monuments such as this have received their share of criticism over the years, in a way Zocchi’s Columbus monument has already received a downgrade. It now stands in the Costanera Norte riverside park, near Jorge Newbery Airfield on the northern edge of the city. However, until 2013 the Columbus monument used to stand in the square directly behind the Casa Rosada, Argentina’s presidential palace. It became controversial for similar reasons as the equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson behind the White House. President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner had the Columbus monument moved to its less-prominent, current location, replacing it with a statue commemorating Juana Azurduy de Padilla, a mixed-race female military commander from the wars of independence.

According to Bienalsur’s website, “Dismantling the legacy of colonialism may require a more complicated solution than removing its symbols and replacing them with new ones.” Creating this new path between destruction and preservation, Alexis Minkiewicz has created his sculpture group La piedad de las estatuas (The Piety of Statues), using recreated parts of the original Zocchi monument as a way to reimagine the original work. The only part of the sculpture group that is radically different from the original monument is Columbus himself. He is shown completely nude other than his shoes and hat, with two octopi covering his genitals and parts of his face. Many have described the figures’ placement as almost orgy-like, reminiscent of the 1814 Katsushika Hokusai print The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife. Looking on from the side are a duo of nude sailors, while the angel originally next to the torch-bearing woman now stands on the roof overlooking the courtyard. Rather than looking ahead, Minkiewicz’s angel seems like he’s stumbled across Columbus and his octopi, adding a touch of voyeurism. His wings have also been removed and are hanging on hooks that, according to Daniel Gigena, make them look “as if they are sides of beef.” In numerous articles, Minkiewicz has said that he is not concerned with Columbus himself. Instead, he has tried to focus specifically on the “carnality” and “erotic potential” of Zocchi’s monument. In creating a new work, there is “a sensation from sculptor to sculptor,” establishing “a dialogue with [the monument’s] creator across time.”

Reactions to Minkiwiez’s sculpture range from a silent chuckle to a baffled eye roll, showing a mixture of contempt and disbelief. Such reactions are unwarranted, and this Argentine artist has contributed a serious, new way to approach the ongoing monuments debate. Minkiewicz has not destroyed or defaced the monument, nor has he preserved it entirely. In the same way that we should neither sanitize nor completely erase our dark and disgraceful historical episodes, Minkiewicz neither keeps nor removes Zocchi’s monument. Like he sought to do, he has reimagined the work, thereby engaging with all those who contributed to the monument’s creation across time and space. Free discourse, even with those who are long gone, is possible, and may be one of the most effective yet underutilized ways to approach these subjects. Hopefully we can follow the example of Alexis Minkiewicz in doing just that.

The Achilles Heel Is Samson’s Foot: Artificial Intelligence In Art Authentication

When it comes to the future of many jobs, one of the most common fears is the advent of automation. The image that often comes to mind is that of robotic arms on an assembly line, repeating the same action continuously without any sign of fatigue. But the manufacturing sector is not the only place where automation may threaten peoples’ job security. Of all the organizations interviewed by McKinsey, 31% are worried about labor displacement because of automation. Because many see automation as an inevitability, there have been efforts to introduce artificial intelligence as a replacement for a great number of jobs, some of which actually require humans. The most recent example I saw is several different companies coming out with their own countertop bartending machines, dispensing Manhattans and Negronis with nothing more than a disposable pod and the push of a button. It seems like the same is being done with art authentication.

Art authentication software got a big win not long ago, when the Guardian reported on September 26th that one of the most prized paintings in London’s National Gallery has been declared a forgery by an art authentication AI. Samson & Delilah, attributed to the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, has been kept at the National Gallery since 1980, when the museum bought it at a Christie’s auction for £2.5 million (nearly £11 million today). Using 148 verified Rubens paintings as a control group, AI software from the Swiss-based tech company Art Recognition reported that there is a 91% probability that Samson & Delilah is a fake.

The AI used by Art Recognition is what is known as a convolutional neural network, which divides a painting into a grid, then analyzes each cell to detect color and brushstrokes patterns. Despite some sources hailing this new technology as a sort of miracle machine ready to replace the actual human experts, the people behind the software have emphasized that this is not the case. Dr. Carina Popovici, one of the co-founders of Art Recognition, has made it clear that the software, while robust enough to detect fakes and forgeries, is best used in tandem with “[c]hemical analysis of pigments or carbon detection” to better aid experts in authentications.

But when one looks at the history of the National Gallery Rubens, it seems like the AI did nothing but tell everyone what most experts already knew. According to records, there was indeed a Samson and Delilah painting created by Rubens around 1610 for the mayor of Antwerp, Nicolaas Rockox. That work was sold to an unknown buyer in 1640 and disappeared from the record not long after. The work in the National Gallery first appeared when the Rubens expert Ludwig Burchard authenticated it in 1929. After Burchard’s death, however, it was revealed that he had knowingly issued certificates of authenticity for fake Rubens paintings in exchange for cash. This revelation threw many of his authentications into doubt, including the one for Samson & Delilah. Furthermore, copies and engravings of the original painting show several major differences between the National Gallery Rubens and what the original should look like. One difference may seem insignificant, but it is one of the most frequently-cited pieces of evidence used by skeptics: a foot.

In the painting, Samson lays asleep in the lap of his lover Delilah as she cuts his hair. Meanwhile, his leg extends to the right-hand side of the canvas until his toes disappear off the edge, out of view. Some Rubens experts have drawn attention to this as evidence that the National Gallery painting is a copy. Human feet are notoriously difficult to draw and paint. Case in point, even the Italian Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli was known for never being able to master the art of painting feet, and consequently left them rather awkward and misshapen in his finished works. Copies and engravings of the original Samson & Delilah show the full foot included in the painting, for good reason. Because feet were so difficult to depict, Rubens made a point to feature them in their full form in many of his works, including Descent from the Cross, The Fall of Man, David Slaying Goliath, and the Three Graces. Despite the evidence accumulated even before the AI analysis, the National Gallery and some Rubens experts continued to assert the work’s authenticity. Details like Samson’s foot may be something that AI might skip over while looking at brushstroke patterns. There are also other factors that make the AI report less significant. The Art Recognition software was programmed only to recognize the characteristics of a Rubens work based on shared traits from a cache of other Rubens works. But the AI was not designed to recognize the characteristics of his studio apprentices that aided in the completion of his works. In the past, some works attributed to Rubens were later identified as created by Jan van den Hoecke, Rubens’s main assistant in the 1630s.

The only response from the National Gallery was a brief recognition of the report: “The Gallery always takes note of new research. We await its publication in full so that any evidence can be properly assessed. Until such time, it will not be possible to comment further.” While AI software should definitely be considered a tool that experts can use in the authentication of artworks, they shouldn’t be thought of as a total replacement. There are some jobs that machines can do very efficiently, but then there are some that require an actual human touch. Which brings me back to those countertop bartender machines. But does that little machine really replace an actual bartender? Can it make recommendations based on your palate, or make witty jokes as it strains your cocktail into a coupe glass, or come up with new drinks based on their own experimentation? While the data collected by AI can be useful, identifying a painting as a forgery involves a lot more than that. Knowing the provenance, getting a look at the back of the canvas, running chemical tests on the pigments, and being intimately familiar with an artist’s entire oeuvre is required to make that kind of judgment. There’s even a healthy bit of instinct involved, or realizing that there’s something that’s not quite right without being able to specify the issue. Until someone can develop artificial intelligence that can do all that, all the experts can rest easy for now.

The Rehs Family

© Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York – November 2021