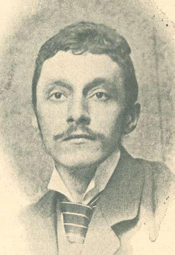

BIOGRAPHY - Geza Vastagh (1866 - 1919)

Géza Vastagh was born into a family of artists and revolutionaries. His father, György Vastagh (1834-1922), was raised in the Hungarian city of Szeged, known today as the home of paprika, but better known in the nineteenth century as a key center for nationalist revolutionary action. The Hungarian Revolution of 1848, like so many others across Europe that year, was spurred by a desire for independence from an imperial government. The Austrian Hapsburg rulers were neither Hungarian nor democratic, nor did they support residents of Szeged in their hope for a government that would reflect the values of the native Hungarian culture. In 1848, György Vastagh joined the local revolutionaries in following Lajos Kossuth, the leader of the nationalistic movement. By 1849, the Hungarians were defeated, the city Szeged having been the last seat of the revolutionary government. György Vastagh would have been only fifteen at this time.

Five years later, when the railway reached Szeged, Vastagh left his hometown for Vienna where he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts. He may also have frequented the private studio of Carl Heinrich Rahl (1779-1843), a classically trained painter who had spent many years in Rome. In 1857, Vastagh completed his studies and moved to Kolozsvár, Hungary. It was here that he married, started a family and developed his own career as a painter. [i]

On October 4, 1866, Vastagh’s eldest son Géza was born in Kolozsvár. Two years later, another son, György the younger, arrived. Like their father, the Vastagh sons’ childhood was marked by political upheaval, largely as a result of the 1848 revolution. Shortly after Géza’s birth, the city and the surrounding region of Transylvania was included in the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, a treaty that reunited the Kingdom of Hungary with the Hapsburg Empire headquartered in Vienna. However, ethnic Romanians, Serbs, and Croats continued to be oppressed and persecuted under the emperor Franz-Joseph until World War I. In contrast, the Jewish population was emancipated under the terms of the 1867 Compromise and subsequently increased rapidly, rising from 776 Jewish households in 1866 to 3,008 in 1870; 1910 there were 7,046 households. [ii]

The cultural and ethnic diversity of Kolozsvár in the 1860s and 1870s was further embellished by the ever-growing pressure of Magyarization, which privileged the Hungarian language above all others. Concurrent with this linguistic bias was a revival of interest in the social and cultural history of the Magyar people; the composer Franz Liszt, for example, made ample use of traditional folk songs in his work as did the poet Janos Arany in his writing. By the closing years of the nineteenth century, this ethnocentric preference would be integrated into the larger design reform movements known as art nouveau. [iii]

Both Géza and his brother György the younger received their first art education from their father, but were sent to Munich in their mid-teens to study at the Academy of Fine Arts. Géza appears to have made his debut at the annual exhibition there in 1883, at age seventeen, which suggests that he began his studies a few years earlier. His debut painting was called Invitation to Fight (Aufforderung zum Kampf). [iv] That same year, he painted a traditional but sophisticated portrait of a girl, entitled Young Girl in a White Dress with a Blue Sash and a Rose. The carefully composed setting and props suggest that this was a commissioned portrait from a comfortably middle-class family. In contrast, a work from 1884 reveals a very different approach. In Bánffyhunyadi-menyecske, a young woman dressed in folkloric costume associated with a region of Transylvania is shown in profile gazing into the distance against a roughly painted stark blue background. Although the figure seems lost in unhappy thoughts, her presence is tangible.

This type of painting no doubt reflects the influence of Simon Hollósy (1857-1918), a fellow Hungarian in Munich who started a private art school in the mid-1880s. Hollósy was critical of the training at the Academy, advocating instead for a Realist approach with a particular emphasis on studying the work of Gustave Courbet in Paris. Although Courbet died in 1877, Hollósy was an ardent advocate of the French avant-garde in the less adventurous arts community of Munich. His influence on Vastagh is evident in the young artist’s new awareness of a more modernist approach to painting as well as his frequent depiction of everyday rural life.

Perhaps because of Hollósy’s influence, Vastagh ventured to Paris in 1885 where he exhibited some of his portraiture. Not yet twenty years old, he received a favorable notice from Alfred de Lostalot in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts. [v] After remarking that most of the Hungarian paintings on display were “un peu mélancolique”, Lostalot observed that Vastagh’s portraits were admirably modeled and marked by a distinctive sentiment that alleviated what the critic perceived as a characteristic Hungarian chilliness. Such positive critical commentary for such a young artist certainly must have encouraged and heartened Vastagh as he began his career in earnest.

Rather than remain in Paris, however, he returned to Hungary, this time to Budapest where his father had established a studio in 1876. The senior Vastagh served as a court painter to Archduke Joseph Karl Ludwig, often receiving commissions for official public buildings such as the Hungarian State Opera; in addition, he maintained his private practice as a portrait painter, increasingly working for local aristocrats. Géza Vastagh painted Playtime in 1886, probably in Budapest; the sitter is unknown, but it is clear that the artist has developed into a sophisticated genre painter. The interior environment is filled with exotic objects—tropical palms, a tiger-skin rug, a small Moorish revival end table and a Japanese fan—all indications that his time in Paris was well spent in absorbing the trends in contemporary art. Although this image is most likely a Hungarian interior, Vastagh does not seem to have lingered there for long; in 1889 he returned to Paris for the grand Exposition Universelle where he again exhibited his work. [vi]

The following year he began traveling to North Africa where he encountered an environment that was radically different from Europe, both culturally and physically. It was there that he started to paint lions, an image that would come to dominate his oeuvre for the rest of his life. He began with a trip to Tunisia and Algeria in 1890, but would eventually expand his scope to encompass large swaths of the Middle East. Simultaneously, he turned his attention to venues in Germany, exhibiting at the Annual Exhibition in Munich in 1890 and the International Art Exhibition in Berlin in 1891; both of these shows were similar to the annual Paris Salon in that they were the most prestigious exhibitions of the year, and generally contained a wide selection of current artistic production. [vii] Vastagh’s entries for both expositions were paintings of animals—lions, ducks, and chickens. The farmyard animals might best be described as Realist genre paintings, but the canvases of lions are anchored in the tradition of animal painters such as Rosa Bonheur.

Vastagh maintained a consistently high profile in both Berlin and Munich until the onset of World War I. He participated in the annual exhibitions regularly and sought out independent commissions as well. One particularly intriguing project was his work for the famous Berliner Tiergarten (the zoo), where he created depictions of many of the larger animals such as lions, tigers, and bears in the years around the turn of the century.

The decade surrounding 1900 was especially productive for Vastagh. He had developed a reputation in several areas—genre painting, portraiture and as an animalier. His work was popular in a variety of international art markets. In 1898, he had three portraits included in a Belgian publication called Portraits du Siècle, 1789-1889, edited by Max Sulzberger of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. [viii] That same year, he participated in a Viennese special exhibition sponsored by the Genossenschaft der Bildenden Kunsttler Wiens (Cooperative of Fine Arts, Vienna).

In 1899, his work is noted in an article in the New York publication, The Collector and Art Critic: “Another notable importation is a large lion’s head by Vastagh Giza,(sic) the Hungrian artist, whose work is scarcely known in this country.” [ix] And turning eastwards, Vastagh participated in an exposition in St. Petersberg and Moscow with a painting titled Lutte de taureaux (Bulls fighting). [x] The Russian expo was part of a program of cultural, economic and industrial exchanges between the tsar’s empire and the French government. It should be noted that this was also one of the international expositions where art nouveau received significant attention. Although Vastagh’s work is unlikely to be described as art nouveau, it nonetheless shares some of the design reform movement’s fascination with exotic and folkloric motifs.

The most significant art event in 1900 was the Exposition Universelle in Paris, where international art nouveau took the center of the stage. From the Pavilon de l’Art Nouveau by Siegfried Bing to the glittering display of Tiffany Studios to the extraordinary performances by modern dancer Löie Fuller, this world fair was without precedent in its extraordinary presentation of the ‘new art’. The fact that Vastagh exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français—and received an honor award—makes it clear that he had achieved a respected position within the international arts community.

Throughout the first decade of the twentieth century, Vastagh continues to expand his horizons. Although his home base was always Budapest, his travels took him back to the Middle East as well as to England where he found yet another art market that supported his work. In 1908 an organization known as London Exhibitions, Ltd. sponsored a special Hungarian Exhibition at Earl’s Court in which Vastagh’s work was prominently featured. Likewise, auction catalogs from these years provide evidence that his paintings had been selling well in England. [xi] A year later, in 1909, Vastagh added Venice to his expanding list of exhibition venues, again submitting his painting to an international art exposition, this time the Biennale di Venezia. [xii]

In spite of the lack of documentation about Vastagh’s personal life, there is ample evidence of a successful career in the exhibition records of the time. His constant traveling suggests that he preferred a peripatetic existence, and his love of animals reveals not only a fascination with the exotic but also with the daily rural life of ordinary people. His work was curtailed by the onset of World War I when travel to “enemy” nations was not permitted. Based on the work that he submitted to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, Vastagh seems to have found abundant subjects for painting in both his sketchbooks from Africa and his native region. Three works were exhibited: Winter in the Atlas Mountains; In the Farmyard; and Hungarian Buffalo Span. He received a silver medal at the Expo. [xiii]

When the war ended on November 11, 1918, the Austro-Hungarian empire collapsed. The former Kingdom of Hungary was again independent, but still torn by the deep ethnic divisions within its own borders. By the time the Treaty of Trianon was signed in 1920, Hungary had lost two-thirds of its territory, a Pyrrhic victory for the generation that fought the revolution of 1848. Géza Vastagh lived to see the end of the war, but died in Budapest on November 5, 1919, before the peace was settled. He was fifty-three years old.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest

Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

[i] The machinations of eastern European rulers in the nineteenth century created a particularly confusing—and ever changing—geopolitical landscape. The city of Kolozsvár is today known as Cluj-Napoca and it is located within the national boundaries of Romania. In Vaspagh’s lifetime, it was part of the Kingdom of Hungary and then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire and was known as Kolozsvár. In the German language favored by the Hapsburg rulers, it was referred to as Klausenberg. In Yiddish, the language of the large Jewish population, it was called Kloyzenburg (קלויזענבורג).

[ii] The Jewish community in Kolozsvár continued to expand until the onset of World War II. The Nazis occupied the city and surrounding region in the summer of 1944 and confined all Jewish citizens to a ghetto. All were deported to Auschwitz between May 25 and June 9, 1944. See: The Open Databases Project of the Museum of the Jewish People at https://dbs.bh.org.il/place/-cluj-cluj-napoca.

[iii] For a fuller discussion of Hungarian culture during these years, see Jeremy Howard, Art Nouveau, International and national styles in Europe (Manchester, UK and New York: Manchester University Press and St. Martins Press, 1996) 103-122.Münchener

[iv] Künstler-Genossenschaft, Illustrierter Katalog der internationalen Kunstausstellung im königl. No. 1741 (Munich: Verlag von Rudolf Mosse,1883) 128.

[v] Alfred de Lostalot, “Exposition de Budapest”, Gazette des beaux-arts, juillet 1885: 256-267

[vi] Catalogue officiel illustré de l’exposition décennale des beaux-arts de 1889 à 1900, No. 140 (Paris:Imprimeries Lemercier et Cie, 1889) 306. Vastagh’s paintings were titled Deux grandes toiles historiques (Two large historical canvases), which unfortunately doesn’t reveal much about their content; nor does it indicate whether this was a diptych or perhaps two pendant paintings.

[vii] See M Münchener Jahres-Ausstellung, llustrierter Katalog der Münchener Jahresausstellung von Kunstwerken aller Nationen im königl. No 1302. (Munich: Franz Hanfstaengl Kunstverlag, 1890). 40; illustrated on page 99. See also Verein Berliner Künstler, Internationale Künst Ausstellung veranstaltet vom Verien Berliner Künstler anlässlich seines funfzigjährigen Bestenhens, 1841-1891 Katalog, Nos. 3491 and 3492 (Berlin: Verlag des Vereins Berliner Kunstler, 1891) n.p.

[viii] Max Sulzberger, (ESNBA) Portraits du Siècle, 1789-1889, Nos. 215, 216, 217, (Schaerbeek: Imprimerie Gerard Richez, 1898) 90.

[ix] Notes”, The Collector and Art Critic, November 15, 1899:19-24.

[x] Catalogue de l’Exposition Austro-Hongroise organisée avec l’autorisationi supérieure de S. M. l’Empereur par les Gouvernements d’Autriche et de Hongrie sur demande de la Société Impériale d’Encouragement des Arts. St-Pétersbourg--Moscou 1899-1900 (Paris, 1899) 11

[xi] See Catalogue of the highly important collection of modern pictures and water colour drawings of the English and continental schools of Stephen G. Holland (London: Christie, Manson & Woods, 1908). Auction catalogue June 25-29, 1908: Lot no. 428: The Monarch of the Forest, 1891. For the Hungarian art exhibition catalgoue, see London Exhibitions, Ltd., Hungarian exhibition: Earl's Court, 1908 (London: Gale & Polde, 1908).

[xii] Biennale di Venezia, VII Exposizione Internazionale d’ARte della città di Venezia Catalogo, vol. no. 8, 1909 (Venice: Premiate Stabilimento C. Ferrari, 1909) Catalogue section: Padigione dell’Ungheria (165-178). Vastagh submitted a painting called Siesta (#78).

[xiii] Catalogue de luxe of the Department of Fine Arts, Panama-Pacific International Exposition, Nos. 490, 492, 492 (San Francisco: P. Elder and Company, 1915) 267.