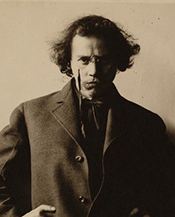

BIOGRAPHY - Bror Julius Olsson Nordfeldt (1878 - 1955)

Bror Julius Olsson Nordfeldt’s career was marked by constant traveling both within the US and internationally. His life began, however, in the hamlet of Tullstorp in the province of Skåne on the southernmost tip of Sweden. Born on April 13, 1878 to Ingrid and Nels Olsson, Nordfeldt spent his first thirteen years in Tullstorp. [i] Although the population of Tullstorp was only 340 in the 2010 census, the size of the local church suggests that it may have been somewhat larger in Nordfeldt’s time.

The family moved to the US in 1891, settling in the large community of Swedish immigrants in Chicago. The change was dramatic. The population of Chicago in 1890 was 1,099,850 people, an increase of 118.6% from the 1880 census; Swedish immigrants accounted for 43,000 of those people. It was an exciting time to be in Chicago where the preparations for the World’s Columbian Exposition were underway when the Olsson family arrived. Like the vast majority of Chicagoans, they probably visited the Fair at least once, perhaps on Chicago Day when attendance was restricted to city residents and no entry fee was required. One of the attractions at the fair was the Palace of Fine Arts, where young Nordfeldt may have seen the prodigious international display of paintings and sculptures from forty-six countries plus the US.

There is scant information about Nordfeldt’s educational experiences, but he may have been apprenticed to a printing company at about age sixteen. If so, he may have been responsible for mixing inks and certainly would have been exposed to typesetting and graphic design as well. Regardless, he enrolled in the School of the Art Institute in 1899 where he studied under John Vanderpoel, a gifted teacher, but also an ardent anti-modernist. It didn’t take Nordfeldt long to realize that he disagreed with that position, even banding together with several fellow students to form an ad hoc Modernist organization known as the Beetles. [ii]

In spite of his advocacy for modernism, Nordfeldt’s skills as a classically trained artist were quite apparent. As a result, he came to the attention of a visiting artist, Albert Herter, who asked if he would like to work on a mural project for the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in the summer of 1899. The project involved creating eight paintings of varying sizes for the McCormick pavilion at the Paris world’s fair of 1900. In these works, it is evident that Nordfeldt had developed a sophisticated sense of composition that reflected the influence of Japonisme as well as traditional Beaux-arts strategies. After spending the summer working in Herter’s Long Island studio, the two men set out for Paris where Herter would oversee the construction of the McCormick pavilion and Nordfeldt would handle the installation of the paintings.

For a young artist, Paris in 1900 was a festival of modernism. The fair introduced art nouveau to the world and the city itself was full of avant-garde exhibitions. Siegfried Bing, who had pioneered art nouveau in his Paris gallery, designed his own pavilion at the fair while Loie Fuller, who was born in suburban Chicago, built a small theatre for her extraordinary dance performances. [iii] Louis Comfort Tiffany dazzled visitors with his favrile glass. And Hector Guimard's now-famous design for the Paris Metro stations opened that summer, bringing art nouveau architecture to the streets of the city. Not surprisingly, Nordfeldt decided that he would stay awhile. He enrolled in the Académie Julian for a brief time, but his aversion to the doctrinaire curriculum—even at the relatively progressive Académie Julian—soon prompted him to open his own studio for potential students; four German students sought out his guidance and successfully submitted their work to the annual Salon the following year. [iv]

The next year found Nordfeldt in Reading, England where he studied with Frank Morley Fletcher, a master printmaker specializing in woodblock printing, and head of the Art Department of University College. [v] Morley was a friend of Albert Herter whom he met when they were students at the Atelier Cormon in Paris in 1888; no doubt, it was Herter who introduced Nordfeldt to Morley and his work. Morley was particularly interested in Japanese printmaking techniques, which is what Nordfeldt hoped to learn from him. [vi] From that point forward, printmaking became a regular part of his practice.

After completing his course of study in Reading, Nordfeldt traveled to Sweden to see family and returned home to Chicago in 1903. He set up his studio at 57th St and Stoney Island Avenue in an emerging artists colony on the south side of the city. The buildings were originally part of the World’s Columbian Exposition, but by 1903 when Nordfeldt rented space there, they were quite dilapidated. One of his fellow tenants, the writer and critic Floyd Dell, described his own studio in a letter to the poet Arthur Davison Ficke. “I have just returned to my ice cold studio, where I have built a fire with scraps of linoleum, a piece of wainscoting and the contents of an elaborate filing system of four years creation. . . . My room contains one bookcase and nine Fels-naphtha soap boxes full of books, a typewriter stand, a fireless cooker, and couch with a mattress and a blanket.” [vii] The discomfort notwithstanding, Nordfeldt, Dell and many others formed a neighborly group of artists, writers and performers as well as several academics from the nearby University of Chicago.

The Jackson Park arts colony—as it was sometimes called—provided a progressive alternative to the more middle-of-the-road arts community clustered around the Art Institute of Chicago downtown. [viii] Although the two communities were generally congenial, there were clear differences of opinion about both art and politics. Politically, the Jackson Park group were disturbed by the social inequality and exploitation of workers that they witnessed daily in Chicago. That concern was often expressed in their work. Aesthetically, their differences were at the heart of Chicago modernism. The definition of the role of the artist—whether painter, poet, playwright or performer—was at the heart of the discussion. Were artists responsible for upholding a European tradition that maintained a classical ideal of beauty and nobility of spirit or were they challenged to reflect the society in which they lived? Should artists encourage their audiences to think about social and aesthetic issues from a new perspective? Nordfeldt’s position was never in doubt; he was a modernist from the outset.

During this period in Chicago, Nordfeldt supported himself as an instructor at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts and as a portrait painter. [ix] His sitters were often the people that he worked with or occasionally other members of the arts colony; Floyd Dell’s portrait, for example, hangs today in the Newberry Library in Chicago. The faculty from the University of Chicago also sometimes commissioned a portrait, such as the well known economist Thorsten Veblen for whom Nordfeldt created two portraits. The painter’s style was heavily influenced by his work with Morley and by the Japanese prints that inspired them both. As would be his practice throughout his life, Nordfeldt's work as a printmaker would consistently inform his work as an oil painter. In 1906, he won his first recognition for a woodblock print at the International Print Exhibition in Milan where he won a silver medal. [x]

By 1907 Nordfeldt was again on the road. He moved to New York where he set up a studio and then accepted an assignment from Harper’s Magazine to provide illustrations from Europe. He was back in Sweden in 1908 and then traveling to Wales, England, France and Italy. In 1909 he was in Tangier where he married Dr. Margaret Doolittle, a psychologist whom he had known in New York and encountered again in Morocco. The newlyweds remained in Europe for another two years as Nordfeldt continued to provide illustrations for Harpers Magazine from both Spain and Italy.

In 1911, they returned to Chicago where Nordfeldt again took up his work as a portrait painter. His sitters included many of the avant-garde leaders of the day such as the novelist Theodore Dreiser, poet Arthur Ficke, Mrs. John Alden Carpenter whose husband was a composer, and the actor Maurice Browne. [xi] In addition to his more lucrative portraiture work, Nordfeldt was absorbed in capturing images of the city itself in a series of etching that he began in 1911. He was fascinated with almost all aspects of daily life; the barges on the Chicago River, smoke-filled skies above the factories, and workers tending an open hearth furnace. These gritty portrayals of the city at work were complemented by depictions of skyscrapers under construction and people gathering for a chat outside a local shop as well as children flying kites and playing on the beach at Jackson Park. In short, he documented the daily life of Chicago’s ordinary people.

Many of these etchings were most likely part of Nordfeldt’s first solo exhibition at the Thurber Galleries in 1912. The show also featured paintings such as Chicago Artists Crossing the Bridge to Hades that demonstrated a strong Fauvist influence in the use of intense color, and a desire to express a mood through abstracted forms. This was work that was unlikely to have been shown in any other gallery either in Chicago or New York at the time. W. Scott Thurber’s gallery had been a well established fixture of the Chicago art scene since the 1880 but in 1909, he hired Frank Lloyd Wright to re-design the interior of the space and began to exhibit contemporary modern art. Thurber hosted the first solo exhibition of Arthur Dove’s decidedly non-representational art in March 1912, thus establishing his intention to showcase modernist artists as well as his more traditional inventory. [xii] The fact that Nordfeldt’s exhibition was mounted shortly after Dove’s suggests that his work was also understood as an expression of a new avant-garde sensibility.

During these last years in Chicago, Nordfeldt and his wife Margaret were also involved in founding the Little Theatre movement. It was at one of the frequent parties held by the artists at the Jackson Park studios that Nordfeldt, Maurice Browne, and Ellen Van Volkenburg began to discuss the idea of a community-based theatre in the neighborhood. Together with several other artists from the area, they were soon rehearsing their first production: The Trojan Women opened to positive reviews in 1912, with sets and costumes by Bror Nordfeldt. Today, Maurice Browne is recognized by theatre historians as the founder of the Little Theatre movement in the US.

Although the early years of the twentieth century were very productive for Nordfeldt—and his scope of work had not only expanded, but had been publicly recognized and respected, he and Margaret were restless by early 1913. They decided it was time for a change and set about planning a return to New York to see the Armory Show followed by an extended stay in Europe. They sailed for France in May 1913. Nordfeldt submitted a painting to Salon d’Automne. In June 1914, a Servian nationalist assassinated the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary in Sarajevo. World War I had begun. Although they had hoped to stay in Paris for five years, the political tensions cut the Nordefeldts’ visit short. They were back in New York living in Greenwich Village that fall. In the bohemian community of the Village, they discovered their old friends Floyd Dell and Mary Heaton Vorse already living there. It was a companionable place for them to settle.

The next few years would be defined by winters in Greenwich Village and summers at the art colony in Provincetown, Massachusetts. At the heart of the Provincetown art colony was the Cape Cod School of Art, founded in 1899 by Charles Webster. In 1914 the newly founded Provincetown Art Association hosted its first annual exhibition, attracting artists from across the country. By 1915, it had become the place to spend the summer for a wide swath of New York artists. The Nordfeldts were no exception, and they were joined by many fellow Chicagoans that they knew from their days working with the Little Theatre. Other visual artists included Charles Demuth, and William and Marguerite Zorach. In short, it was a gathering of like-minded artists from a variety of disciplines.

Like so many good ideas, the concept of the Provincetown Players was first proposed at a party. Reminiscences about the Little Theatre in Chicago prompted someone to suggest that the group should put on a play in Provincetown. On July 15, 1915 they did just that on the veranda of Neith Boyce and Hutchins Hapgood’s home. The minimalist set was designed by Nordfeldt. The enthusiastic response from the audience led to a discussion about doing more plays—one-act scripts only—and finding a better space to perform. A run-down shed on the wharf was offered as a possibility and the group began immediately to remodel it into a theatre. The Provincetown Players was born.

For the next two years, the Nordfeldts were part of this seminal group in American theatre. They acted, designed and produced as part of the loosely organized group. Nordfeldt did most of the sets, often in partnership with Charles Demuth. And he occasionally acted as well, his most notable role being the upstart “post-Impressionist” painter in George Cram Cook’s satirical script Change Your Style. In the summer of 1916—in the newly remodeled theatre—the Provincetown Players produced a series of one-act plays ranging from a spoof of Tom Sawyer by the socialist playwright John Reed and the first production of a script titled Bound East for Cardiff by an unknown actor named Eugene O’Neill.

Sadly, the Provincetown Players did not survive the power struggles and in-fighting that began when they attempted to incorporate their efforts into a theatre based in New York. After a prolonged and increasingly contentious schism left the theatre with only fourteen members, they stopped producing plays. Nonetheless, the influence of this experimental theatre company has been far-reaching and enduring. As theatre historian Brenda Murphy notes ““The Provincetown Players was the most significant and the most influential American theatre group of the early twentieth century. It was the first theatre group in the United States with a serious artistic agenda, which included the production of new plays by American playwrights and the employment of innovative and experimental production methods.” [xiii]

The Nordfeldts’ life in New York was punctuated by trips to other parts of the US, most notably a trip to New Mexico in 1918 to visit an old friend, William Henderson, in Santa Fe. The impressions made by the southwestern landscape and the indigenous culture that they were introduced to during this trip would prove to be indelible. A year later, they left New York for good and moved to Santa Fe. Once there, Nordfeldt would begin one of his most ambitious projects yet—building his own house.

His confidence in his own construction skills was undoubtedly based in part on his success as a set designer for the Provincetown Players, but his fascination with creating an environment that would be aesthetically consistent in every way was grounded in the work of art nouveau designers. The concept of a totally designed environment saw its earliest expression in the work of William Morris and Philip Webb at the Red House in 1859. Through Morris’s prodigious writings and lectures, the concept spread quickly, emerging in France as art nouveau design which Nordfeldt knew well. As a participant in the Paris International Exposition in 1900, he would have been well aware of the excitement generated by the art nouveau artists and designers represented at the fair—and of the concept of aesthetically harmonious interior architecture.

The house is a simple adobe and stone structure with a timber-roofed front porch. Both inside and outside, Nordfeldt carved the lintels and decorative wooden details. In addition, he designed metalwork elements such as the front door knocker. And in keeping with his love of collaboration and enjoyment of aesthetic and political discussions, he purchased the site in a neighborhood where other artists had already settled.

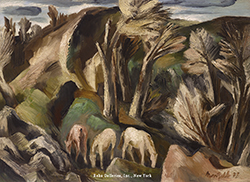

Nordfeldt remained in Santa Fe for twenty years. His work from this period shows a thought-provoking intersection between cubist and occasionally surrealistic tendencies and the landscape and customs of Santa Fe and its surrounding region. Antelope Dance, one of his earliest paintings in his new home, references dancers from the nearby San Ildefonse Pueblo in the midst of a traditional performance. The structure of the composition and the looming mountain in the distance echoes nothing so much as Paul Cézanne’s bathers with Mont Set.-Victoire in the background. Similarly, Santa Fe Houses #46 from 1924 is clearly a southwestern landscape painted as abstracted blocks and shapes reminiscent of cubism. In contrast, his etchings from the mid-1920s are highly detailed and realistic works showing local residents and locales. In the 1930s, he turns increasingly to still life painting, creating a synthesis of rather traditional images of flowers and fruit placed on tilted tabletops against curiously vacant backgrounds. Perhaps this is Nordfeldt’s version of surrealism?

In 1931, Nordfeldt once again accepted a teaching position, this time at Utah State College. Next, he taught courses at the Wichita Art, Association and, in 1933, he was hired as a guest lecturer at the Minneapolis School of Art. In these midwestern cities, he found new material for his artwork, savoring his return to locales where there were four seasons and a more varied color palette. In Minneapolis particularly, he painted a number a winter scenes; in addition he created color lithographs featuring snow covered fields or ice skaters enjoying the day.

The local press was quite supportive of Nordfeldt’s work. An article by John K Sherman in the Minneapolis Star would have an unexpected impact on the artist’s life. On April 27, 1935, Sherman wrote: “Probably the most vitalizing influence which has entered the lives and conditioned the objectives of local painters in recent years is that personified by the rubicund and waggish B.J. O. Nordfeldt, the Strong Man from the Southwest, a painter’s painter if ever there was one, an artist with more to say, verbally and plastically, than any other man who ever squinted over a canvas at the Minnesota scene.” [xv] This review would result in several new students enrolling in Nordfeldt’s advanced painting class at the Minneapolis School of Art. One of them was Emily Abbott, with whom he would begin a long correspondence after returning to New Mexico in 1936.

Nordfeldt’s fascination with Santa Fe and the southwest was rapidly waning in the wake of his teaching stints in Wichita and Minneapolis. He began to spend an increasing amount of time in and around Lambertville, New Jersey, just across the Delaware River from the New Hope, Pennsylvania arts colony. The location was recommended to him by his friend Vaclav Vytlacil who had studied at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago from 1906-1913 and then taught at the Minneapolis School of Art; he and Nordfeldt may have met in either of those locations. As always, Nordfeldt enjoyed the companionship of fellow artists. The proximity to the east coast galleries was another plus, and in 1937, he signed with the Van Diemen-Lilienfeld Galleries of New York. [xvi] At this point, Nordfedlt moved permanently to Lambertville, separating from his wife Margaret Doolittle.

Throughout this period Nordfeldt had maintained a correspondence with his former student, Emily Abbott. In 1941, however, Emily stopped writing. It was not until Nordfeldt contacted her in 1944 during a serious bout of depression that the two once more began to communicate. His letter arrived just shortly after the death of her father when Emily too was feeling despondent and alone. Their letters soon turned into a courtship and after divorcing Margaret in 1944, he and Emily were married in Minneapolis. [xvii] Nordfeldt returned to teach one last semester at the Minneapolis School of Art in the fall of 1944. Meanwhile, the couple had purchased a farm south of Lambertville. The only building on site was a deteriorating barn, which they managed to remodel sufficiently to make it habitable when they left Minneapolis in late 1944. And then they began planning their new house. It was an eclectic mix of international style modernism and idiosyncratic carvings by both Emily and Nord as well as some elements from the Santa Fe house. From this base, the couple continued to travel and to paint.

Over the next decade, Nordfeldt would occasionally accept teaching assignments and it was in April of 1955 that he and Emily traveled to New Mexico for that purpose. In Henderson, Texas on April 21, Nordfeldt died of a heart attack. He has just turned seventy-seven a week earlier.

After his death, Emily devoted herself to creating and protecting Nordfeldt’s legacy through generous donations of his work and endowments to further art education for students.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

Selected Museums

American Swedish Institute, Minneapolis

Art Institute of Chicago

Harvard Museums, Cambridge, MA

Hirshhorn Museum of Art, Washington, DC

James A. Michener Art Museum, Doylestown, PA

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Minnesota Museum of American Art, St. Paul, Minnesota

Museum of Modern Art, New York

University of New Mexico Art Museum, Albuquerque, NM

Newberry Library, Chicago

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, NC

Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis

Wichita Art Museum, Wichita, KS

Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI

Notes

[i] Olsson was his father’s last name, but Bror began using “Olsson-Nordfeldt” as his professional name early in his career. Nordfeldt was his mother’s birth name, and by the early twentieth century, he dropped “Olsen-Nordfeldt” in favor of B. J. O. Nordfeldt on his artwork. See Coke Van Deren, Nordfeldt, the Painter, (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1972) 135-137. It should be noted that Coke Van Deren’s publication on Nordfeldt was the sole source of detailed information about the artist until the 2021 publication of the exhibition catalogue for the retrospective of his work at the Wichita Art Museum and the Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis. See Gabriel P. Weisberg, ed., B. J. O. Nordfeldt, American Internationalist (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021).

[ii] The other founding members of the Beetles were John Norton, Albert Krehbiel, Harry Townsend, and Harry Osgood. Cited in Charlotte Moser, “‘In the Highest Efficiency’: Art Training at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago,” in The Old Guard and the Avant-garde: Modernism in Chicago, 1910–1940, ed. Sue Ann Prince (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990) 198. The source for this information is a manuscript by Thomas W. Tallmadge, “John Warner Norton:1876–1934” from January 1935. See note 14, p. 261.

[iii] Margaret Haile Harris, “The Dancer, the Artist and the Critic: A Celebration of Loïe Fuller by Pierre Roche and Roger Marx.” The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1890-1940, no. 3 (1979): 15–24. (http://www.jstor.org/stable/41806215).

[iv] Coke Van Deren, Nordfeldt, the Painter, (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1972) 135-137.

[v] For a fuller discussion of Nordfeldt’s extensive printmaking work, see Annika Johnson, “Nordfeldt as Printmaker” in Gabriel P. Weisberg, ed., B. J. O. Nordfeldt, American Internationalist (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021) 32-55. Exhibition catalogue.

[vi] Morley would later write a definitive book on Japanese printmaking techniques. See Frank Morley Fletcher, Wood-block Printing: A Description of the Craft of Woodcutting & Colourprinting Based on the Japanese Practice (London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons, Ltd., 1916)

[vii] The original letter can be found in the Floyd Dell Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago. Floyd Dell, letter to Arthur Davison Ficke, May 26, 1913.

[viii] Janet Whitmore “Bror Julius Olsson Nordfeldt and Modernist Chicago” in Gabriel P. Weisberg, ed., B. J. O. Nordfeldt, American Internationalist (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021) 19-54. Exhibition catalogue.

[ix Paul Kruty, ”Mirrors of a “Post-Impressionist” Era: BJO Nordfeldt’s Chicago Portraits,” Arts Magazine (January, 1987): 27-33.

[x] Coke Van Deren, Nordfeldt, the Painter, (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1972) 135.

[xi] The Chicago Renaissance in literature has received considerably scholarly attention, most recently in Liesl Olson’s book on the subject. See Liesl Olson, Chicago Renaissance, Literature and Art in the Midwest Metropolis (New Haven, NJ: Yale University Press, 2017).

[xii] Ann Lee Morgan, “‘A Modest Young Man with Theories’: Arthur Dove in Chicago, 1912” in The Old Guard and the Avant-garde: Modernism in Chicago, 1910–1940, ed. Sue Ann Prince (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990) 23-37.

[xiii] Brenda Murphy, The Provincetown Players and the Culture of Modernity (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005) xiii.

[xv] John K. Sherman, “Nordfeldt Show is Called Vital Display of Oils,“ Minneapolis Star (April 27, 1935): 26. See also Gabriel P. Weisberg, B. J. O. Nordfeldt, American Internationalist (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021)13. Exhibition catalogue.

[xvi] The Van Diemen-Lilienfeld Galleries (21 E. 57th St, New York) handled primarily old masters, but expanded its repertoire to include contemporary French, German and other modernist artists in the mid-1930s. Van Diemen Gallery, which had long been based in Berlin, was destroyed by the Nazis in 1936. At that time, Van Diemen moved his business to New York where Lileinfeld Gallery had been located since 1925. For more information see the Frick Museum’s Center for Collecting at: https://research.frick.org/directory/detail/270 See also the Van Diemen-Lilienfeld Galleries archives at the National Gallery, Washington, DC at: https://library.nga.gov/discovery/fulldisplay/alma991764133804896/01NGA_INST:IMAGE

[xvii] For a full discussion of Emily’s role in Nordfeldt’s life and legacy, see Paul Kruty, “Emily and Nord: An Enduring Partnership” in Gabriel P. Weisberg, ed., B. J. O. Nordfeldt, American Internationalist (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021)56-64. Exhibition catalogue.